Last Wednesday (March 20) in Overture Hall,

Alonzo King’s LINES Ballet and Hubbard Street Dance Chicago celebrated their

temporary merger. The unusual combined

program revealed a formidable gulf between the two decidedly different dance

companies, and an elegantly constructed bridge across it.

On the bill were one

substantial work by each troupe plus by a piece King choreographed for both

together, fashioned from a difficult long-distance process that involved two

brief in-the-flesh meetings and lots of communications via YouTube and email. First up was LINES’ 40-minute “Rasa” (2007),

which rose miles above the rest of the program.

“Rasa,” like all of King’s visionary ballets, is a work straight from

the heart, built on a rich, complex score by tabla master Zakir Hussein, whose world beat / classical approach mixed percussion instruments, droning

sitar, chants, and the syllabic rhythms that lie behind all tabla playing. Other choreographers, including current Ailey

artistic director Robert Battle and Madison’s own Li Chiao Ping have used Sheila

Chandra’s “Speaking in Tongues” Indiapop takes on vocalized tabla, which drive movement in similarly percussive ways.

And other dance companies have brought Indian temple art to life

onstage. Probably the best of these is

the soulful Nrityagram Dance Ensemble, an India-based folkloric collective

dediated to the spirit, philosophy and theory of classical Indian dance

arranged for contemporary theater.

But King goes where no

choreographer has gone before. He turns the

Hindu deities – the many-limbed Krishnas and Shivas and Durgas, flexing their

feet and wrists – into pure

abstractions, telling untold but universal myths. Their story specifics and

cultural accoutrements – the elephant trunks, beads and polychrome paint – are

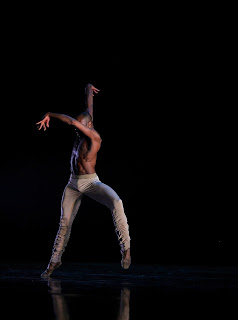

stripped away. Under shifting conditions

of golden light, King’s remarkable dancers, in brief, neutral toned dancewear, resonate

with Hussein’s score. Their fluidity

breathes vibrant life into the angular poses and flexed appendages of

temple art. Elasticity originates deep in the dancers’ cores, legs spidering

into space, pairs of arms whipping through light creating the optical illusion

of many.

None of this movement

would be imaginable without exquisite ballet training, and yes, the western

classical vocabulary is there too, in all its glory – luxurious attitude turns,

pique turns in sixth, outrageously extended penché arabesques, pas de chats and

brisés, entrechat six, chaine turns, flying second position split leaps, more.

The deities’ allegories –

their struggles and unities – emerge onstage. Within shifting groups pairs of

dancers merge, male and female aspects of a single god. In the fifth movement the very powerful

Keelan Whitmore, conjuring Agni, lord of sacrifice and fire, leaps and spins

like raging flames, his many arms stretching toward infinity.

It would be wrong to call

“Rasa” performance. It’s a piece of pure

dance, entirely lacking artifice. It seemed akin to tribal ritual, or the way

you might dance yourself, at home alone with the volume turned up. You might spot it in a nightclub where a pair

of extraordinary salseros, loose and totally unselfconscious, are dancing right

on clave. The immense difference between

almost all of us and King’s company, of course, is natural balletic ability,

flawless technique, and awe-inspiring stamina.

On the heels of “Rasa,”

Hubbard Street resident choreographer Alejandro Cerrudo’s “Little Mortal Jump”

(2012) fell flat. If “Rasa” was a

universal abstraction of Hindu theology filtered through the language of

western classical dance, “Little Mortal Jump” was a Euro-American abstraction

of dance numbers in a generic broadway show. The shift in focus was anticlimatic, the drop

in energy precipitous.

Still, within those

parameters, Cerrudo’s piece had its charms.

Hubbard Street dancers are very proficient at the quirky contemprary

vocabulary they’re known for. The piece,

full of magic tricks with giant moveable black cubes, wove a series of pas de

deux through sections in which larger groups prevailed. The first pas de deux was

flirtatious; later, a pair of dancers in heavily velcroed suits stuck

themselves to the cubes, then stripped away the suits to return to the floor. In the final pas de deux the previously cool

light went golden. The man (the names of

the soloists in each movement weren’t listed in the program) lifted the woman

high overhead, upside down; under the bright light this seemed deftly surreal. The two dancers ran, circling each other,

under bright spots; then, like alien abductees, they disappeared into a golden passageway

that opened up amidst the cubes, which, being spun through space by other

dancers, leant a satisfyingly hallucinatory feel to the end of this dance.

In “Azimuth,” the raison

d’etre for the entire evening, King worked miracles, pulling all the stops out

of Hubbard Street’s dancers and merging them with LINES. “Azimuth” looked like a LINES work, albeit

one with slightly tamer technique – though the sheer number of bodies onstage

(28 rather than 12) was arresting enough to compensate.

“Azimuth” is a big,

meditative work rich with unison flow, though LINES’ dancers generally stood

out. The men of the two companies

blended better than the women; four Hubbard Street men were especially stunning

in a very active section with LINES’ Keelan Whitmore and Ricardo Zayas.

There were a few rough

edges – not surprising in a work mostly made long-distance. Smart, minimal

dancewear showed off the remarkable mix of bodies, and the lighting was lush. But

the score – an odd jumble of original music by Bay Area composer Ben

Judovalkis, Russian liturgical songs, spirituals, and other sounds – sometimes

got in the way. And – unlike the crystal

clear concepts in “Rasa” – King’s abstraction of azimuth, a geometric angle

between an observer, a point of interest, and true north – didn’t pop out till

the end. In King’s personal book of

cosmic geometry, azimuth is the distance between where a person stands, where

his or her attention is fixed, and how that separation is obliterated. The achievement of pure dance – the merging of

choreography and spirit that’s a hallmark of King’s works, including this one –

is a manifestation of azimuth, though a subtle one.

What nailed the notion was

the final pas de deux between LINES’ Meredith Webster and David Harvey. In it were echoes of “Rasa”’s couplings, neatly

bookending the program. Webster and

Harvey pushed and pulled each other, then obliterated the separation; when she

sat on his shoulders they became – they didn’t impersonate, they became – an

eight-limbed being. Other bodies lay

upstage in the dark, moving shapes barely seen.

Against this mysterious backdrop Webster and Harvey separated

physically, but their energies went on flowing together – the two, beyond

shadow of doubt, were one.

That’s azimuth, as King

defines it, to a T.

No comments:

Post a Comment